Congenital heart defect repair refers to the range of surgical and interventional procedures designed to correct structural abnormalities in the heart that are present at birth.

What are the types of congenital heart defects?

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) represent a diverse group of structural problems present at birth that affect the heart’s anatomy and its ability to function effectively.

One of the more common defects ispatent ductus arteriosus (PDA), where a vital fetal blood vessel known as the ductus arteriosus fails to close after birth, allowing blood to pass abnormally between the aorta and pulmonary artery.

Equally significant iscoarctation of the aorta, a narrowing of the aorta that disrupts normal blood flow, leading to increased blood pressure in the upper body and diminished circulation in the lower body.

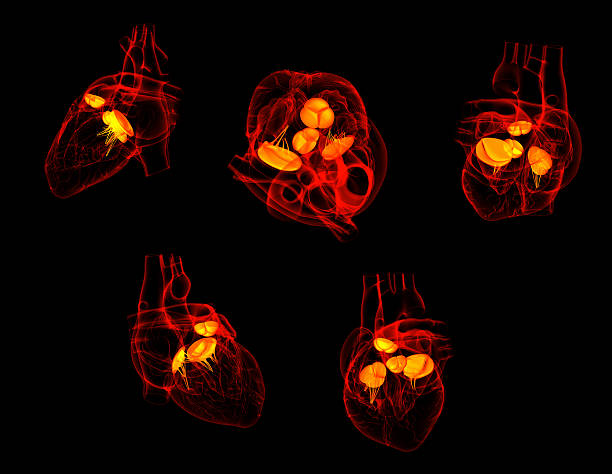

Defects involving the heart’s septa are also widespread. Anatrial septal defect (ASD)is characterized by a hole in the wall between the two upper chambers (atria), while aventricular septal defect (VSD)involves a hole between the lower chambers (ventricles); both conditions permit the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, placing extra strain on the heart.

More complex conditions include cyanotic defects such asTetralogy of Fallot, which encompasses four abnormalities—VSD, pulmonary stenosis, right ventricular hypertrophy, and an overriding aorta—culminating in reduced oxygen delivery to the body.

Intransposition of the great vessels, the positions of the aorta and pulmonary artery are essentially switched, creating parallel circulatory systems that severely reduce oxygenation necessitating rapid intervention.

Additionally,truncus arteriosusis a rare defect where a single arterial trunk emerges from the heart instead of two separate vessels, impairing normal circulation, while tricuspid atresia results from the absence of a fully formed tricuspid valve, hindering blood flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle.

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR)occurs when the pulmonary veins connect abnormally, diverting oxygen-rich blood away from the left atrium, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome—one of the most severe defects—features an underdeveloped left side of the heart, critically limiting the pumping capacity necessary for systemic circulation.

Each of these defects requires a nuanced approach to diagnosis and treatment, underscoring the complexity and variability of congenital heart anomalies and the importance of early intervention to optimize long-term outcomes.

How is congenital heart defect diagnosed?

Diagnosingcongenital heart defects(CHDs) involves a comprehensive evaluation that integrates clinical examination with an array of advanced diagnostic tests to accurately delineate the heart’s structure and function.

Initially, prenatal screenings such as fetal ultrasound and fetal echocardiography can identify potential abnormalities before birth, offering critical early insights into a developing heart.

After birth, physicians begin with a thorough physical examination, where the presence of abnormal heart sounds or murmurs may raise the suspicion of an underlying defect. The cornerstone of postnatal diagnosis is the echocardiogram, a non-invasive test that uses sound waves to generate real-time images, allowing clinicians to assess chamber sizes, valve function, and blood flow patterns.

Complementing this, an electrocardiogram (ECG) is often performed to evaluate the electrical activity of the heart, which can reveal arrhythmias or conduction issues associated with structural anomalies.

A chest X-ray can further aid in the evaluation by revealing the overall heart size and shape, as well as any changes in the pulmonary vasculature that accompany certain defects.

Together, these diagnostic modalities allow for a comprehensive assessment of congenital heart defects, ensuring accurate diagnosis and guiding the subsequent therapeutic interventions required to optimize long-term outcomes for patients.

Should someone with congenital heart defects exercise?

People with congenital heart defects (CHDs) can often benefit from regular exercise, as physical activity improves cardiovascular efficiency, strengthens muscles, and enhances well-being. However, the amount and type of exercise must be customized to an individual’s specific heart condition and medical history.

Many individuals with mild CHDs can safely engage in moderate aerobic activities such as walking, swimming, or cycling, which improve circulation and reduce cardiovascular risks. For those with more complex defects, exercising under the supervision of a healthcare provider or within a cardiac rehabilitation program is essential to ensure safety. Before beginning any exercise regimen, patients should undergo a thorough evaluation—including stress tests and echocardiograms—to determine their exercise tolerance and establish safe activity levels. Healthcare professionals may advise against high-intensity workouts or contact sports that could strain a fragile heart. With appropriate guidance, exercise programs can be tailored to promote improved heart function.

When is surgical repair of a congenital heart defect advisable?

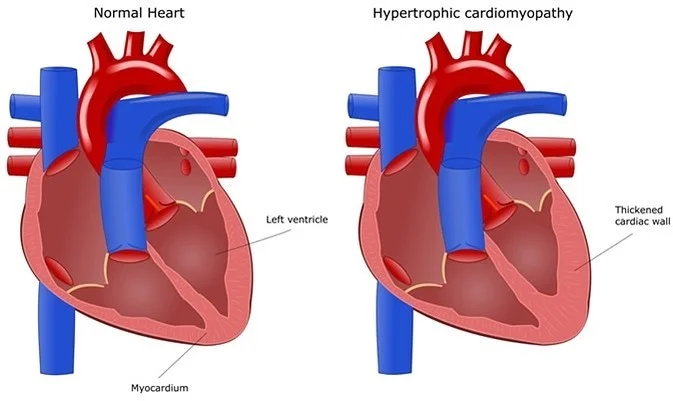

Determining when surgical repair of a congenital heart defect is advisable depends on several critical factors, including the type, size, and severity of the defect, as well as the presence of symptoms and overall heart function. Surgical intervention is often recommended when the defect causes significant disruption of blood flow, leading to symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, poor growth in children, or recurrent respiratory infections. In these cases, medical management alone may not suffice to prevent long-term complications like heart failure, arrhythmias, or irreversible damage to the heart muscle. Timely repair is essential for infants and young children, as early intervention can promote normal cardiac development, enhance their quality of life, and reduce the risk of future morbidity. Advanced diagnostic tools, including echocardiograms, cardiac MRI, and cardiac catheterization, are crucial for evaluating the defect’s impact on the heart and guiding treatment decisions. For older patients or those with less severe defects, surgical repair may be advised when there is clear evidence of deteriorating heart function or an increased risk of complications if left untreated.

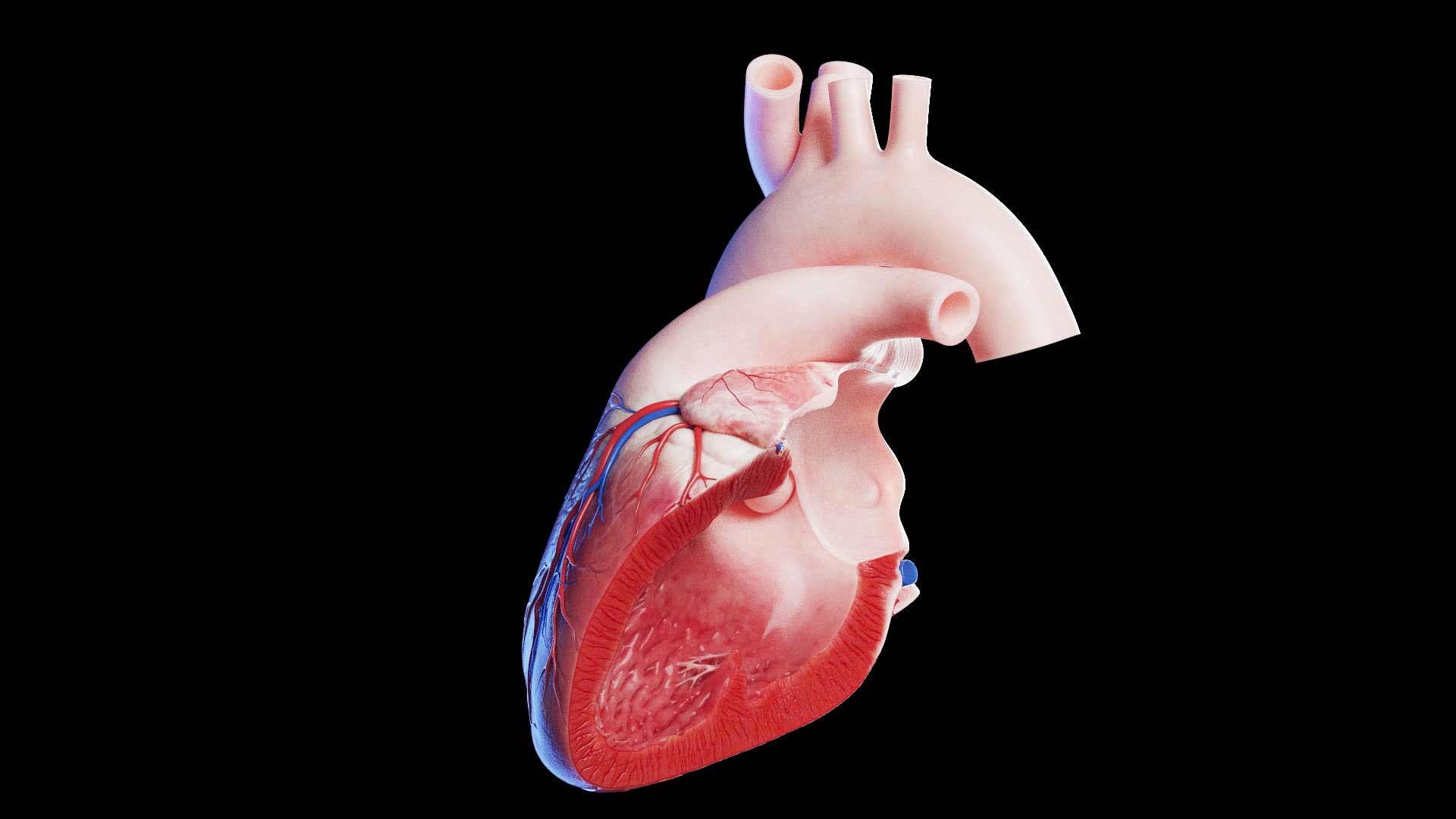

How is repair of a congenital heart defect accomplished?

Repair of a congenital heart defect is accomplished through a range of treatment options that are carefully tailored to the patient’s unique condition, anatomy, and overall health. In many cases, traditional open-heart surgery is the primary approach. During this procedure, the heart is temporarily stopped and supported by a heart-lung machine, allowing the surgeon to access the heart directly. With a clear view of the defect, the surgeon can close holes in the heart wall using patches, reconstruct abnormal valves, or reroute blood flow by connecting vessels with greater precision. In recent years, less invasive techniques have gained popularity.

Transcatheter interventions allow doctors to repair certain defects using catheters inserted through small incisions in the groin. Devices such as occluders can be deployed to close septal defects, while stents are used to widen narrowed arteries. Minimally invasive surgeries, which utilize smaller incisions and specialized instruments, further reduce recovery times and surgical risks. A multidisciplinary team, including pediatric or adult cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, carefully evaluates each case to determine the most appropriate strategy. Postoperative care, along with regular follow-up evaluations, is essential in ensuring that the repair is successful and that the patient’s heart function improves over time for longevity.

Congenital heart defect surgery risks

Congenital heart defect surgery, while often life-saving, carries inherent risks that patients and caregivers must consider before proceeding.

As with all major surgeries, complications such as bleeding, infection, and adverse reactions to anesthesia remain potential concerns throughout the perioperative period.

Due to the intricate nature of congenital abnormalities, these procedures can also increase the likelihood of arrhythmias or disturbances in heart rhythm during and after the operation.

Manipulation of delicate cardiac tissues may inadvertently injure nearby structures, such as coronary arteries or conduction pathways, resulting in compromised blood flow or rhythm issues.

Furthermore, the use of cardiopulmonary bypass can trigger inflammatory responses and coagulopathy, posing additional challenges in managing blood clotting.

Postoperative recovery may be complicated by wound infections, delayed healing, or respiratory difficulties, particularly in patients with other underlying conditions.

Ultimately, a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach is essential to minimize risks and optimize outcomes for patients undergoing congenital heart defect repair.

Congenital heart defect repair recovery & aftercare

Recovery from congenital heart defect repair is a gradual and carefully managed process that extends well beyond the operating room. In the immediate postoperative period, patients are typically monitored in an intensive care unit, where close observation of heart function, wound sites, and overall vital signs ensures early detection of any complications. As patients transition out of intensive care, the emphasis shifts to comprehensive aftercare, which includes tailored cardiac rehabilitation programs designed to gradually reintroduce physical activity while building strength and endurance. These programs often integrate light aerobic exercises and monitored physical therapy to help restore cardiovascular function and improve overall fitness. At home, recovery involves strict adherence to medication regimens—such as blood thinners or heart medications—to manage heart workload and prevent clot formation, along with meticulous wound care and lifestyle adjustments, including improved nutrition and stress-reduction techniques. Regular follow-up appointments and diagnostic tests, such as echocardiograms and EKGs, are critical for monitoring progress and adjusting treatment plans as needed. Emotional support through counseling or support groups can also play a vital role, as patients navigate the psychological challenges associated with major surgery. Committed, structured aftercare not only facilitates optimal healing but also empowers patients to resume daily activities safely, promoting long-term heart health and enhancing their overall quality of life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, congenital heart defect repair procedures represent a pinnacle of modern medical innovation, offering transformative solutions to complex cardiac challenges from infancy through adulthood. These procedures, ranging from traditional open-heart surgeries to minimally invasive catheter-based interventions, have evolved significantly over the years, improving outcomes by addressing a wide spectrum of structural heart abnormalities. Advances in diagnostic imaging and preoperative assessments now enable clinicians to tailor interventions to the unique anatomical and physiological needs of each patient. This individualized approach not only minimizes surgical risks and enhances recovery but also underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary team in ensuring optimal long-term results. While the journey from diagnosis through recovery demands careful management and persistent follow-up, the benefits of these repairs are profound, often providing patients with the opportunity to achieve near-normal cardiac function and a vastly improved quality of life.

Read More