Strawberry hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors that typically emerge within the first weeks of life, presenting as bright red, raised “strawberry-like” plaques on the skin.

What is a strawberry hemangioma?

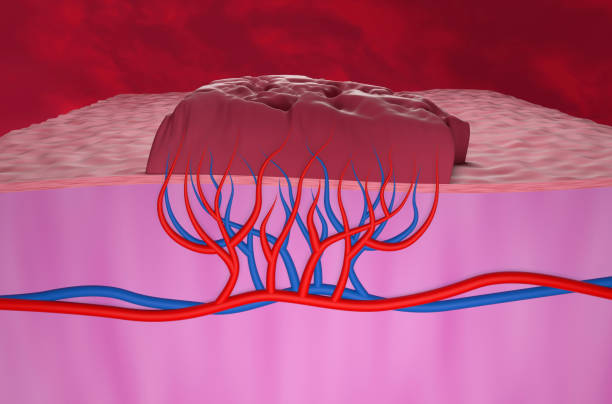

Strawberry hemangiomas, or infantile hemangiomas, are benign vascular tumors composed of a dense cluster of proliferating capillaries that typically emerge within the first weeks to months of life. These lesions present as bright red, raised plaques—resembling the surface of a strawberry—most often appearing on the face, scalp, or neck, though they can occur anywhere on the body. Following initial appearance, hemangiomas enter a rapid growth phase during the first six to twelve months, with the bulk of their enlargement completed by three to five months of age, after which they gradually involute over several years. By the child’s fifth birthday, approximately 70 percent have begun to regress, and up to 90 percent resolve without intervention by age ten. While most strawberry hemangiomas remain small and pose no functional issues, larger or strategically located lesions—especially those near the eyes, airway, or over joints—may ulcerate, bleed, or interfere with vision and movement, warranting medical evaluation. Diagnosis relies on clinical examination, with imaging reserved for deep or complicated variants, and treatment options range from watchful waiting to systemic beta-blockers likepropranolol, laser therapy, or surgical excision in refractory cases.

What are the types of hemangiomas?

Hemangiomas encompass a heterogeneous group of benign vascular tumors distinguished by their timing of appearance, depth within the skin, and growth behavior.

The most familiar subtype, infantile hemangioma, arises in the first weeks after birth and follows a characteristic triphasic course: a rapid proliferative phase, stabilization, then gradual involution over years.

Superficial infantile hemangiomas—often called “strawberry” hemangiomas—present as bright red, raised plaques; deep lesions appear bluish, soft, and subcutaneous; mixed hemangiomas combine both features.

In contrast, congenital hemangiomas are fully formed at birth and subdivide into rapidly involuting congenital hemangiomas (RICH), which regress within the first year, and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (NICH), which persist unless treated.

Beyond infancy, capillary and cavernous hemangiomas describe vessel architecture: capillary forms consist of small, tightly packed capillaries in the dermis, while cavernous hemangiomas feature larger, blood-filled vascular spaces.

Recognizing these types is essential for anticipating natural history, selecting first-line treatments such as propranolol or laser therapy, and determining whether observation, medical management, or surgical intervention is most appropriate.

What causes strawberry hemangiomas?

Strawberry hemangiomas, or infantilehemangiomas, emerge from proliferating endothelial cells that form dense capillary networks within the skin. While their exact origin remains unclear, a leading theory points to a placental origin: hemangioma tissue and placenta both express the glucose transporter GLUT1, suggesting placental cell embolization to fetal skin during gestation. In addition, in-utero hypoxia may trigger angiogenic pathways—via hypoxia-inducible factors and vascular endothelial growth factor—to spur endothelial proliferation. Several perinatal factors increase risk: female infants are two to three times more likely to develop hemangiomas, and those born prematurely, at low birth weight, or as part of a multiple birth have higher incidence rates, implicating perinatal stress and vascular insults in pathogenesis. A familial tendency hints at genetic predisposition, though no definitive mutation has been identified. Hormonal influences, particularly estrogen’s pro-angiogenic effects, may also contribute to the female predominance. Ultimately, these multifactorial triggers—placental anomalies, hypoxic stress, hormonal drivers, and inherited susceptibility—converge during early infancy to initiate the rapid proliferative phase characteristic of strawberry hemangiomas, setting the stage for their subsequent involution over the first decade of life.

Strawberry Hemangiomas in adults

Adult “strawberry hemangiomas” in adulthood are more accurately termed cherry angiomas or senile hemangiomas. These benign capillary proliferations arise spontaneously after age 30 and present as small (1–5 mm), round to oval, bright red to purple papules that may be flat or slightly raised, most commonly on the trunk, arms, and shoulders. Unlike infantile hemangiomas, they do not undergo a lifecycle of proliferation and involution; instead, they persist indefinitely and often increase in number with advancing age, affecting up to 75 percent of individuals over 75 years old. Although their exact etiology remains unclear, factors such as genetic predisposition, aging-related vascular remodeling, and environmental triggers like sun exposure and mechanical irritation have been implicated. Cherry angiomas are typically asymptomatic but can bleed if traumatized. Treatment is unnecessary unless requested for cosmetic reasons or recurrent bleeding, with removal options including pulsed-dye or CO₂ laser ablation, electrocautery, and shave excision with electrodessication. Patient education should emphasize the benign nature of these lesions, the low risk of complications, and simple home monitoring strategies such as photographing lesions periodically. While generally innocuous, sudden changes in size, color, or the new appearance of multiple lesions warrant dermatologic evaluation to exclude other vascular anomalies or systemic conditions.

What are the risk factors for strawberry hemangiomas?

Strawberry hemangiomas most often arise in infants who share certain epidemiologic and perinatal characteristics. Female babies are two to three times more likely than males to develop these vascular tumors, suggesting hormonal or genetic influences in pathogenesis. Prematurity and low birth weight (under 5½ pounds) also heighten risk, possibly due to in-utero hypoxia and immature vascular regulation triggering angiogenic pathways. Multiples—twins, triplets, or higher-order births—experience higher hemangioma rates, reflecting the combined stresses of preterm delivery and placental anomalies. Infants of white race show greater incidence compared with other ethnicities, though hemangiomas can occur across all populations. Emerging data implicate maternal smoking during pregnancy as an environmental contributor, as tobacco-induced placental insufficiency may promote endothelial proliferation. While a definitive genetic mutation has not been identified, familial clustering raises the possibility of inherited susceptibility. Other proposed risk factors include preeclampsia and placenta previa—conditions linked to placental embolization theories—and elevated estrogen exposure, which may enhance capillary formation. Recognizing these risk factors allows pediatricians to monitor high-risk newborns closely, ensuring early evaluation and, when necessary, timely intervention with propranolol, laser therapy, or surgical options to mitigate complications such as ulceration or functional impairment.

Strawberry hemangioma symptoms & diagnosis

Strawberry hemangiomas typically present within the first few weeks of life as bright red, well-circumscribed, raised plaques that may feel warm and spongy to the touch. During the proliferative phase—most rapid between one and five months of age—lesions often enlarge and become more nodular, sometimes developing overlying telangiectasias or superficial ulcerations if traumatized. Deep or mixed hemangiomas can appear bluish, with a firm, subcutaneous component, and may exert mass effect on adjacent structures. Although most remain asymptomatic, lesions in periorbital, airway, or anogenital regions warrant prompt evaluation due to potential visual, respiratory, or functional compromise. Diagnosis is primarily clinical: a detailed history notes timing of onset and growth pattern, while physical examination assesses size, depth, compressibility (blanching under gentle pressure), and anatomic risk factors. Dermoscopy can highlight characteristic lacunar vascular patterns, whereas ultrasound—often the first‐line imaging modality—differentiates hemangiomas from vascular malformations and quantifies lesion depth and flow dynamics in ambiguous cases or when visceral involvement is suspected (particularly if more than five cutaneous hemangiomas are present). MRI is reserved for complex or deep lesions threatening critical structures.

How are strawberry hemangiomas treated?

Treatment of strawberry hemangiomas balances the lesion’s natural tendency to involute against potential complications, with most uncomplicated hemangiomas managed by watchful waiting since roughly 90 percent resolve without intervention by age ten. When treatment is indicated—due to ulceration, rapid growth, or risk to vision, breathing, or feeding—oral propranolol (2–3 mg/kg/day) has become first-line, harnessing beta-blockade to induce vasoconstriction, downregulate vascular endothelial growth factor, and accelerate involution. For small, superficial plaques, topical timolol 0.5 percent gel or patches can offer similar benefits with minimal systemic exposure. Historically, systemic corticosteroids were used to curb proliferation, but they’re now reserved for refractory cases or contraindications to beta-blockers. Adjunctive laser therapies, particularly pulsed-dye laser, target residual telangiectasias and facilitate healing of ulcerated areas, while deeper lesions may respond to long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Surgical excision or curettage is reserved for rare hemangiomas that fail medical and laser management or leave fibrofatty residua causing functional impairment or significant deformity. Throughout treatment, close monitoring by a multidisciplinary team ensures dosing safety, assesses lesion response, and tailors interventions to achieve optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, strawberry hemangiomas epitomize a unique pediatric vascular phenomenon: they emerge early, grow rapidly, then slowly recede, leaving most children with little more than a faint remnant by school age. While the vast majority require no more than periodic observation, identifying high-risk lesions—those that ulcerate, threaten vision or breathing, or leave functional deficits—allows timely intervention. First-line beta-blocker therapy (oral propranolol or topical timolol) has revolutionized management, and adjunct lasers or surgery address stubborn or residual tissue. With an understanding of their natural history and a collaborative, individualized treatment plan, families and clinicians can navigate these lesions confidently, ensuring optimal cosmetic and functional outcomes.

Read More